|

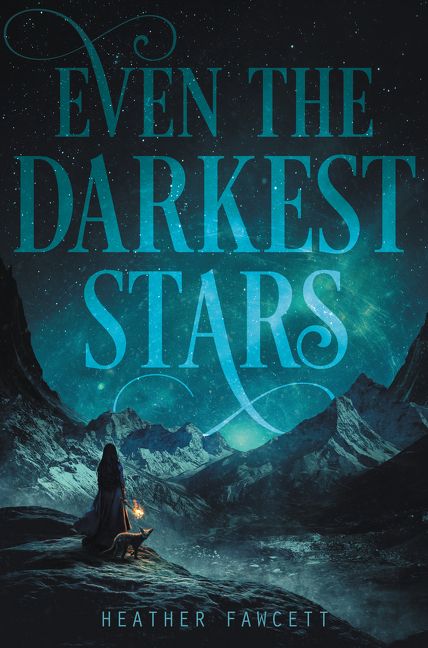

PART I

AZMIRI

ONE

I STRETCHED MY hands over the dragon eggs, focusing all my concentration on their indigo shells, and murmured the incantation. The air rippled and shimmered.

I can do this. The thought was born of desperation rather than confidence. My fingers were frozen, my stomach growled, and my legs ached from hours sitting cross-legged. Behind me, the sheer slopes of Mount Azmiri, draped with cobweb clouds, rose to greet the gray sky. Beyond the narrow ledge I crouched on, the mountainside fell away as if hewn by an ax. The forest far below was hidden under waves of mist, with only a few treetops floating above the surface like skeletal ships. The wind stirred my hair and slid its long fingers down the collar of my chuba. I shivered. The faint light gathering over the eggs flickered and died.

Chirri smacked me on the back of my head, causing me to drop my talisman, a string of ravensbone beads. “Foolish girl! Don’t break your concentration. You’ll never get it right that way.”

“I’ll never get it right any way,” I muttered.

She smacked me again. Perhaps she thought I would do better if my brains were rearranged. “This is the simplest resurrection spell I can teach you at your level. Do. It. Again.”

I made a noise halfway between a sigh and a growl. The incense burning beside the clutch of lifeless eggs tickled my nose, and I pressed my lips together. If I sneezed, Chirri would make us go inside, into her cramped, airless hut, with its smell of burned herbs and its shelves lined with poorly cleaned animal skulls. Sending a silent prayer to the spirits, I looped the talisman around my hands, shook the beads over the eggs, and began the incantation again.

After several moments, Chirri let out an exasperated cry. “Are you speaking the words correctly?”

“Yes, Chirri,” I said, straining to keep the anger from my voice. “I’m speaking the words correctly. I’m focusing my mind. I’m doing everything right, and I’m still a completely useless apprentice.”

“You are wasting time with this obstinacy, Kamzin.”

“We’ve been here since dawn,” I snapped, losing my temper at last. “Trust me, the last thing I want to do is waste time.”

The old woman smiled, the folds of her many wrinkles deepening, and I cursed my foolishness. Chirri was never angry, not truly—she merely used it as a ploy to make others reveal their weaknesses.

“You will stay here,” she said slowly, “until every egg has hatched. Or until the glaciers rise up and cover the village, or the witches return to the mountains in search of human souls.”

Chortling at my expression, Chirri untucked her legs and drew herself to her feet, arranging her many shawls with exaggerated care. Then she retreated toward her hut, which perched higher up the mountainside on an even more precarious ledge. From there, she would watch me until I did as I was told.

Or froze to death.

I glared at the eggs, as if my incompetence was their fault. With a growl, I stretched my aching limbs, then settled in to try again. A bead of sweat trickled down my neck.

“Hshhh,” came a low voice behind me. “Is she gone?”

I whirled. “Tem!”

To my astonishment, my best friend’s head poked up over the side of the ledge. He must have climbed sideways from the terraces, finding footholds and handholds in the weathered granite of the mountainside.

“Er—Kamzin?” he said. “Could you give me a hand? My fingers are numb.”

Bracing my foot against a rock, I hauled him onto the ledge. He collapsed on the ground, panting.

“How long were you down there?”

“Only since your fiftieth try,” he said. I tried to punch him, but he rolled away, laughing. His handsome face was flushed with cold, and his hair, which usually hung low over his forehead, obscuring half his features, stuck out every which way. I couldn’t help laughing too. I had never been happier to see him in my life.

“You look like a rooster,” I said.

He blushed, running his hands through his hair so it would curtain his face again.

“You’d better hurry,” I said, glancing over my shoulder. The clouds were advancing up the slope, sweeping over us in lacy bands. Chirri had vanished, as had her hut. “This weather won’t hold.”

He gazed at me uncomprehendingly. “What are you talking about?”

“You know what—you have to help me with these eggs.”

“I can’t.” His face went white. “Chirri will know.”

“She won’t. She won’t even know you were here.”

He glanced from me to the eggs, then back at me again. “But she’ll never believe—”

I grabbed his shoulder. “It doesn’t matter if she believes it or not. It just has to happen, so I can get out of here. Please, Tem. I’m going crazy.”

He glanced from me to the eggs. I could see him weighing his fear of Chirri against his desire to help me. “All right,” he said finally. “But Chirri can’t know I can do this. Or my father.”

I nodded. Tem’s father worked for my own father, as his head herdsman. He was a dour, sharp-tempered man who was gentler with a misbehaving yak than he was with his son. Tem was supposed to follow in his footsteps, and his father wouldn’t be pleased to learn that his true talent lay in shamanism, not husbandry.

Tem took the talisman, winding the beads around his fingers, and began to chant. He seemed to change, in that moment—something in his bearing and demeanor shifted slightly, and he became almost a stranger.

I shivered. I had watched Tem work spells before—he often helped me practice, in secret—but I had never entirely grown used to it. He murmured the incantation in the shamanic language confidently, absently, with none of his usual self-consciousness, and I could feel the power gather like a storm. The ravensbone made a shivery sound that seemed to vibrate the air.

The eggs glowed. The glow turned to flickering, like sunlight through branches. Cracks appeared in the shells, and then, suddenly, they burst apart.

The baby dragons were the size of sparrows, with long, snakelike bodies supported by six squat legs. They began chittering almost immediately, shaking their damp wings in the breeze. The little lights they carried in their bellies flickered on and off. These were thin and colorless when the dragons were young; as they aged, they would gradually darken and take on color—commonly, an iridescent blue or green.

“Stand back,” Tem said. He murmured again to the largest dragon, which let out a questioning chirp. As one, the dragons spread their wings and took flight. They swirled around us in a tumult of wind and feathery scales, making me shriek and laugh. Then they zoomed away like a glittering arrow, their lights bouncing through the clouds.

“Where are they going?” I said.

“I sent them to Chirri.”

I doubled over with laughter, imagining Chirri’s reaction when the baby dragons swarmed her hut, hungry for milk and teething on her furniture.

“Why aren’t you here in my place?” I said, shaking my head. “You should be Chirri’s apprentice. You’re as powerful as her.”

“Because my father isn’t the elder,” Tem said. “And no, I’m not as powerful as Chirri.”

“Near enough,” I said lightly, sensing the mood shift. My apprenticeship to Chirri had always been a sore point between us. The truth was, Tem would have made a far better shaman for our village than me. But Azmiri’s shaman was always a relation of the elder, usually a child or younger sibling—a way of consolidating power, which would surely backfire spectacularly with me. Tem, as gifted as he was, was a herdsman’s son. It was unheard-of for someone like him to assume such an important position in the village.

“Come on,” I said, grabbing his hand. “Let’s go find some breakfast.”

We flew down the rubbly slope of the mountain, leaping over boulders and grassy knolls with practiced ease. As we came within view of the village, the cloud lifted, revealing huts of bone-white stone huddled against the mountainside, threaded with steep, narrow lanes. The southern half of the village was newer and more uniform than the rest, the huts less eroded and roofed with pale terra-cotta tiles. They had been constructed two centuries ago, replacing those destroyed by the terrible fires that had swept through Azmiri.

We took a shortcut through the orchard, and I leaped up to snatch an apple from one of the boughs. It wasn’t the season yet, and the flesh was painfully tart, but I didn’t care. I was hungry enough to eat my own boots.

The terrain rose again, and I scrambled up the hill. The earth fell away on one side. Across the valley, the mountains Biru and Karranak shoved their snowy heads into the clouds. A familiar feeling welled up inside me—the feeling that I could leap across the valley and come to rest lightly on one of those other peaks. As if I could dig my toes and fingers into the wind and scale it as I had scaled so many earthbound things.

I was ahead of Tem, and didn’t at first hear him yelling. I turned, laughing breathlessly, running backward now.

“What did you—” I began, then let out a cry. I stumbled over a rock and landed hard on my elbows.

All I could see was color. A cacophony of color, green and red and purple and blue. It filled the sky like a monstrous cloud. But as I opened my mouth to scream, the thing resolved itself into a shape—a balloon.

A hot air balloon, sweeping silently over the mountainside. I could make out several small figures silhouetted on the deck, gazing down at me like haughty ravens. The balloon’s shadow passed over me, and I shivered.

Tem reached my side. “You all right?”

I nodded, and he helped me to my feet. We watched the vessel drift over the village, slowly descending until the deck came to rest on one of the barley terraces. The massive balloon sagged to the ground, obscuring our view of the occupants.

“Spirits!” was all I could say.

Tem made a dismissive noise. “River Shara travels in style. He’s probably full of enough hot air to power that balloon himself.”

I stared at him. “River Shara?”

“Ye—”

“The River Shara? You’re telling me that was the Royal Explorer?”

“I think so. I—”

“The greatest explorer in the history of the Empire?”

“Well, I don’t know if he’s—”

I grabbed his arm, excitement flooding me. “Why didn’t you tell me he was coming?”

“I only heard of it yesterday, from one of the traders. You should have known, anyway—why didn’t Lusha tell you?”

“Oh, of course,” I said, with exaggerated understanding. “I forgot that you haven’t met my sister.”

Tem rolled his eyes. “All right. But I’m sure she and Elder have known about this for weeks.”

“Of course they have.” I kicked at the top of a tree poking over the edge of the cliff. Somewhere below, a vulture let out an angry squawk. “They wouldn’t think to tell me. What in the world would the Royal Explorer be doing here?”

Emperor Lozong had many explorers in his employ—men and women, mostly of noble blood, charged with mapping his vast and mountainous empire, spying on the barbarian tribes that threatened his southern and western borders, and charting safe paths for his armies. As his territory expanded, the emperor relied increasingly on explorers to provide him with vital information, not only about the lands he possessed, but also those he wished to conquer. My mother, Insia, had been one of them, though her connection to the nobility was so distant that it would have counted for little at court. River Shara, on the other hand, belonged to one of the oldest noble families, one with close blood ties to the emperor himself. He had earned the official title of Royal Explorer—the most powerful position at court, rivaling even the General of the First Army—after leading a harrowing expedition beyond the Drakkar Mountains in the farthest reaches of the Empire, scaling mountains and glaciers and cheating death countless times. Though many men and women had occupied the position of Royal Explorer, few were spoken of with the same reverence as River Shara.

Tem was shaking his head. “Maybe the emperor sent him to make sure we’re still here, and if not, to update the maps.”

I snorted. It wasn’t an unlikely idea. High in the Arya Mountains at the eastern border of the emperor’s lands, we rarely received visitors from the distant Three Cities. When we did, it was the talk of the village. Even a band of cloth merchants was cause for a banquet.

And this was no mere merchant.

My heart pounded. “I have to meet him. I have to talk to him.”

Tem had been speaking—about what, I didn’t know, for I hadn’t been listening. He fell silent, his expression troubled. “Kamzin—”

“This could be my chance.” I didn’t have to explain what I meant—from the look he wore, he understood well enough. He knew how I jumped at the opportunity to join my father’s men on their hunting trips in Bengarek Forest. How I spent my free days climbing the neighboring mountains. How, when my mother was alive, I had begged her to take me along on her expeditions, and how I still spent many evenings poring over her maps of strange and distant lands, tracing the faded lines of ink with my fingers. I wanted to be an explorer more than anything in the world. I wanted to traverse glaciers and map wilderness and sleep under a roof of stars. I wanted to push against the world and feel it push back.

“So what are you going to do?” Tem said. “Walk up to the Royal Explorer and ask him to please bring you along on his next expedition? Offer to carry his pack or massage his feet?”

“I don’t know what I’m going to do.” I twisted my fingers through my braid. It smelled like Chirri’s incense. “I have to think.”

“What you should be thinking about is your lessons with Chirri,” Tem said. “Not impressing some noble from the Three Cities.”

“And where will that get me?” I felt my temper rise. “Tem, I’m seventeen years old, and I’m still only a junior apprentice. Chirri refuses to make me her assistant, and you know what? I don’t blame her. I hate magic—I’m terrible at it. You know I can’t do this for the rest of my life, no matter what my father says.”

“You’re terrible at magic because you don’t try,” Tem said, giving me an exasperated look. “Anyone can do magic. You get better the more you work at it. It’s like any skill—weaving, or running, or anything else.”

What Tem said was true enough, to a point. Anyone could do magic, provided they had the right talismans and knew the incantations. But there were some who, for whatever reason, took to it more naturally than others. Who possessed an affinity no amount of training could match. That was Tem—it would never be me.

“You know I’m no good at running,” I pointed out. “My legs are too short. I always finished last when we used to race each other. It’s like that with magic—there’s a part of me that’s too short, or too small, and nothing is ever going to change that.”

“You’ve improved since I started helping—”

I turned away. “You’re not listening.”

“I always listen to you,” he said. “I doubt you’ll be able to say the same for River Shara. He’s known for many things, but listening isn’t one of them.”

I scowled. I knew River Shara’s dark reputation—everyone did. Stories of his merciless assassinations of barbarian chieftains, his intolerance of weakness in his traveling companions. He was said to have stranded men and women who had proven too weak to keep up with him, and not all of them made it back to the Three Cities.

I also knew that most stories were like the shadows painted by the late-afternoon sun: deceptive and exaggerated. I wasn’t going to be afraid of stories.

Tem gazed at me for a long moment. Then he sighed. “What do you want me to do?”

I leaped into his arms, wrapping him in a tight hug. “I knew I could count on you.”

He pushed me away, trying and failing to hide the blush spreading across his cheeks. “Have I ever told you how crazy you are?”

“A few times,” I said. “Look on the bright side—if I become a famous explorer, I’ll take you on my expeditions.”

“So I can traipse around in the wilderness, sleeping on rocks and roots and half freezing to death?” Tem snorted. “I’d rather herd yaks.”

“No, you’d rather be Chirri’s apprentice.” I regretted it instantly. A shadow crossed Tem’s face, and he ducked behind his curtain of hair.

“Anyway,” I said, “I’m going to talk to Lusha. Maybe she’ll know what this is about.”

“She’s Lusha,” Tem said. “She knows everything. Whether she’ll be in a sharing mood is another question.”

|

10

10

1

1